Ceiling condensation happens when your warm, moist indoor air meets cooler ceiling surfaces, pushing humidity to its dew point and turning vapor into droplets. Temperature differences, insulation gaps, and airflow limits let surfaces stay cold enough to condense. Activities like cooking, showering, and breathing raise moisture, while poor ventilation concentrates it near ceilings. Insulation and air sealing decisions matter, as do vents and window drafts. Tackle hidden moisture risks, and you’ll uncover where the problem begins—and what to fix next.

Understanding Condensation on Ceilings

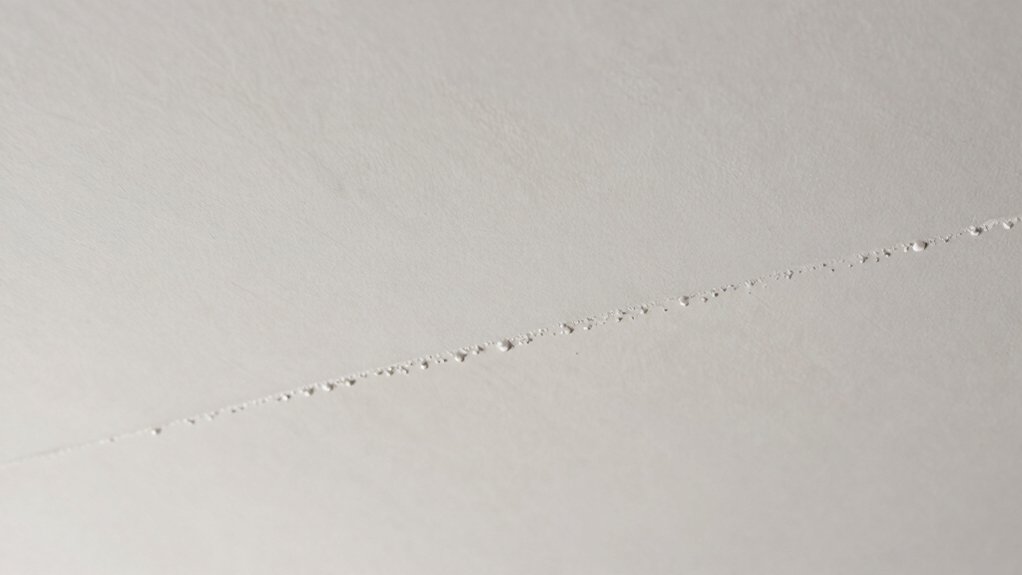

Condensation on ceilings occurs when warm, moist air contacts a cooler surface and releases water vapor as liquid. You observe the interface between air temperature and surface temperature, yielding a saturated vapor pressure that exceeds what the surface can absorb.

In practical terms, you’re tracking heat transfer rates, surface emissivity, and relative humidity to predict condensation onset. You determine that supply of moisture into the space, combined with limited ventilation and thermal stratification, raises local dew-point proximity at ceiling levels.

You assess material properties—insulation R-value, thermal conductivity, and surface roughness—that influence heat flux and nucleation sites. You distinguish short-term moisture spikes from persistent conditions by measuring ambient temperature, humidity, and airflow patterns, then correlating them with observed surface wetness.

How Humidity Becomes Condensation

Humidity becomes condensation when water vapor in the air cools and loses enough energy to shift from a gaseous to a liquid phase at a surface or within a space. You observe vapor molecules migrating toward cooler regions, where ambient energy fails to sustain them in a gaseous state.

As temperatures approach the dew point, kinetic energy decreases, facilitating molecular clustering into droplets on surfaces or within pores. Relative humidity governs the available moisture; high values increase the likelihood of contact with supersaturation and nucleation sites.

Surface characteristics—material, roughness, and cleanliness—influence condensation initiation and droplet distribution. Airflow, pressure, and localized cooling modulate residence time and droplet growth.

In this subtopic, focus remains on the moisture-to-liquid transition mechanics, independent of broader temperature gradient considerations.

The Role of Temperature Difference

When the temperature difference drives heat flow across a surface, condensation occurs more readily because the local air near the surface cools faster than its surroundings, lowering the surface’s dew point relative to the adjacent air.

You observe that heat transfer from warm to cool regions creates a transient boundary layer where air reaches its dew point, initiating microdroplet formation. The magnitude of this effect depends on temperature gradient, surface thermal conductivity, and air movement.

A steep gradient or still air yields rapid cooling at the surface, increasing condensation likelihood on ceilings. As convection strengthens, the boundary layer thins, reducing dew point depression near the surface and delaying condensation.

Effective mitigation targets surface insulation, contact quality, and airflow management to minimize localized cooling below ambient dew points.

Common Indoor Moisture Sources

You’re exposed to indoor humidity sources that add moisture directly, such as cooking, showering, and running humidifiers.

Moisture transfer paths then move that water vapor through ceilings and walls, influenced by temperature differences and air movement.

Identifying these sources and paths sets the groundwork for quantifying their contribution to ceiling condensation.

Indoor Humidity Sources

Indoor humidity originates from several common sources within living spaces, including cooking, showering, laundry, and occupants’ respiration. You measure how these activities release water vapor into the air, altering relative humidity and dew-point relationships.

Cooking elevates vapor fast; ventilation controls diffusion and condensation risk, especially with simmering or boiling.

Showers add high moisture loads in short durations, creating transient spikes that saturate nearby surfaces if exhaust isn’t present.

Laundry, particularly indoors, emits moisture during washing and especially drying cycles, increasing sustained humidity levels until air exchange lowers it.

Occupants’ respiration contributes a steady, predictable baseline, driven by metabolic rate and occupancy density.

Temperature and air movement modulate humidity impacts by affecting vapor pressure and mixing.

Understanding these sources informs targeted mitigation without conflating transfer pathways.

Moisture Transfer Paths

Moisture transfer paths in indoor environments occur through both bulk air movement and surface interactions, enabling water vapor to move from sources to spaces where it can condense or alter humidity. You identify three channels: infiltration and exfiltration, mechanical ventilation, and interstitial or convective transport within materials.

Infiltration brings outdoor moisture indoors via leaks; exfiltration carries interior vapor outside, altering humidity gradients. Mechanical systems, like fans and exhausts, create directed airflows that transport vapor rapidly between rooms or from kitchens and baths to elsewhere.

Surface interactions involve sorption, desorption, and diffusion within wall assemblies, insulation, and furnishings, which regulate transient humidity peaks. Understanding transfer paths helps you predict where condensation risks arise, design appropriate controls, and evaluate retrofit options for improved moisture management without overcorrecting indoor climate stability.

Ventilation: The First Line of Defense

Ventilation acts as the first line of defense against ceiling condensation by controlling humidity levels and removing moist air from enclosed spaces. You regulate indoor moisture by exchanging warm, humid air with drier exterior air, reducing vapor pressure near cold surfaces.

Mechanical and natural systems differ in control precision, response time, and measurement capability; select based on occupancy, climate, and building use. Key metrics include air changes per hour (ACH), moisture load, and dew point interaction with surface temperatures.

Targeted strategies minimize stagnant pockets where vapor concentrates, ensuring consistent dilution and transport away from ceilings. Balanced operation prevents over-ventilation, which wastes energy and can cause comfort issues.

Continuous monitoring with sensors supports optimization, enabling you to adjust flow, filtration, and duct integrity to suppress condensation risk.

Insulation and Air Sealing Impacts

Insulation and air sealing directly shape condensation risk by controlling surface temperatures and limiting heat loss paths. You evaluate how insulation thickness, material conductivities, and installation quality affect thermal bridges and surface dew points.

Effective insulation reduces warm-ceiling temperature gradients that drive moisture condensation, while minimizing thermal bridges at joists, penetrations, and edges lowers localized cold spots. Air sealing complements this by reducing infiltrating moist air that cools surfaces and supplies latent moisture to the ceiling cavity.

You should quantify insulation performance with R-values appropriate to climate and apply continuous coverage to avoid gaps. Match air barrier continuity to framing to prevent air leaks behind soffits or in attic crevices.

Proper detailing, verification, and compatible materials guarantee predictable surface temperatures and condensation control.

The Effects of Poor Ventilation in Windows and Vents

Poor ventilation in windows and vents undermines indoor air quality and condenses moisture on interior surfaces. Inadequate air exchange raises humidity near glazing and cabinetry, promoting surface deposition and potential mold growth. You’ll observe elevated dew points at thresholds of doors and around skylights where stagnant air pockets form, increasing condensation risk during heating cycles or rapid temperature shifts.

Mechanical systems or operable openings that underperform fail to remove moist air, allowing relative humidity to persist above optimal 40–60 percent ranges. Poorly designed exhaust paths can create backdrafts, drawing humid air into living spaces instead of exhausting it.

Consequently, you experience thermal discomfort, increased energy use, and accelerated material degradation. Accurate assessment demands flow-rate measurements, room-by-room humidity profiling, and verification that supply and exhaust balance align with occupancy patterns.

Identifying Hidden Moisture Risk Areas

Hidden moisture risk areas aren’t always obvious. You should map high-risk zones by examining envelope integrity, interior moisture loading, and vapor diffusion paths. Focus on spaces with intermittent humidity spikes (bathrooms, kitchens, laundry alcoves) and on assemblies lacking continuous vapor barriers or proper insulation.

Identify connections between conditioned and unconditioned spaces, noting junctures at ceilings, mechanical penetrations, and roof/wall interfaces where condensation can accumulate. Scrutinize thermal bridges, air leakage paths, and surface temperatures below dew point, using infrared scans or spot measurements to corroborate data.

Prioritize areas with historic condensation events, observed staining, or efflorescence in porous substrates. Document material susceptibilities (gypsum, plaster, wood, drywall clips) and the impact of occupant behavior on latent loads, ventilation schedules, and moisture buffering.

Practical Steps to Prevent Ceiling Condensation

Therefore, to prevent ceiling condensation, align indoor moisture loads with appropriate ventilation, control surface temperatures, and seal air leaks at ceiling junctions and penetrations.

You should assess humidity sources from kitchens and bathrooms, then implement continuous exhaust or heat-activated ventilation to maintain dew-point separation from cold surfaces.

Model surface temperatures using exterior insulation quality, ceiling thickness, and insulation gaps, and adjust to keep the ceiling above the local dew point under peak occupancy.

Tighten building envelope with gasketed drywall joints, mechanical seals, and airtight ceiling penetrations for pipes and fixtures.

Maintain steady indoor temperatures and avoid rapid temperature swings that drive condensation.

Monitor humidity setpoints, perform regular inspections, and repair leaks promptly to sustain long-term control.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Ceiling Condensation Occur Year-Round in Warm Climates?

Yes, you can experience ceiling condensation year-round in warm climates, though it’s less common; you’ll notice persistent humidity and cooler surfaces, which encourage moisture deposition. Euphemistically, humidity travels inward, meeting chilly ceilings, triggering subtle dampness despite warm days.

How Does Humidity From Indoor Plants Impact Ceilings?

Indoor plants increase humidity, raising condensation risk on ceilings by boosting near-saturation air and reducing evaporation. You’ll notice more water droplets, potential mold, and faster paint or drywall deterioration when indoor moisture isn’t managed and ventilation remains poor.

Do Ceiling Vents Reduce Condensation on Rough-Textured Ceilings?

Ceiling vents can reduce condensation on rough-textured ceilings by improving air exchange, which lowers surface temperature differentials. In homes with high humidity, you’ll see up to a 20–30% drop in moisture accumulation when vents are properly sized and placed.

Can Ceiling Condensation Cause Structural Damage Over Time?

Yes, ceiling condensation can cause structural damage over time. You expose framing to prolonged moisture, promoting rot, mold, and wood decay; ongoing dampness also weakens joists and fasteners, risking sagging ceilings and potential structural failure if unchecked.

Are There Quick DIY Tests to Detect Hidden Moisture Above Ceilings?

Yes. You can perform quick DIY tests like moisture meters, gypsum board probing, and infrared imaging for hidden moisture above ceilings, plus checking for discoloration and mildew growth; document readings and monitor over weeks to confirm trends.